Toronto Globe and Mail

“RAFAL ZIELINSKI AND THE ZEN OF FILMMAKING”

TORONTO GLOBE AND MAIL

by Judy Stone

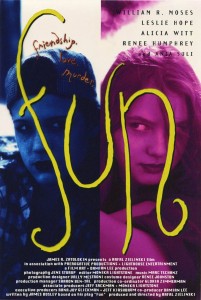

IN PERSON/ The director of Fun thinks film-goers shouldn’t be so quick to judge his unflinching look at two girls who murder an old woman just for kicks.

PLENTY of artists over the years have been entranced by The Tibetan Book of the Dead,but Rafal Zielinski is probably the only one who thinks he can make a contemporary film inspired by it. Meanwhile, he’s pondering how the tenets of Zen Buddhism just may apply to his current movie, Fun.

With its unflinching look at the behaviour of two adolescent girls who murder an old woman, just for the heck of it. Fun is anything but. Still, Zielinski, a former Torontonian, thinks audiences shouldn’t be so quick to judge.

In his film, Zielinski presents the girls’ crime from two points of view. The first, shot in color, tries to show the “thrill” the girls experienced. “It was exciting and fun at the same time.” The second shot in stark black and white, depicts what Zielinski calls “society’s point of view,” namely that the murder “was absolutely horrific and immoral” and therefore deserving of punishment. “From these contrasts, I tried to create a question mark in the viewers’ minds which forces them to think and analyze, which haunts them, as opposed to just walking out of the theatre, having seen it one way or the other.”

At the same time, the Zen Buddhist in Zielinski prompts him to observe: “There is no good or evil. They are all equations of the same thing. I feel that what they did was evil, [yet] to them, it was a, cleansing of all the evil that had happened to them. Maybe my role as an artist is to show both sides and question them.”

Based on the play by James Bosley, Fun is, of course, not the first film to muse on the murderous goings-on of troubled young people. Among others, there have been Terry Malick’s Badlands in 1973, Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers last year and, most recently, Peter Jackson’s Heavenly Creatures. Indeed, Fun, released in Canada last week, has been somewhat over-shadowed by the hoopla attending the release of Creatures, largely because the latter is based on a true story, and one of its juvenile murderers now enjoys a career as a successful mystery writer under the name Anne Perry.

Still, Zielinski reports that the careers of his two young stars, Renée Humphrey and Alicia Witt, have “taken off like rockets” since Fun was screened, and won two Special Jury Awards for Acting, at the influential Sundance Festival earlier this year, and was nominated for two Spirit Awards, Humphrey was chosen to play another strange teenager in Lawrence Kasdan’s French Kiss, co-starring Meg Ryan and Kevin Kline. She is also a co-star in Kevin Smith’s absurdist comedy Mall Rats. Witt, meanwhile, is co-starring as Madonna’s lover in Quentin Tarrantino’s coming Four Rooms and plays one of Richard Dreyfuss’s students in Mr. Holland’s Opus.

In Fun, Witt plays Bonnie, 14, a hyperkinetic product of family neglect; Humphrey’s Hillary, 15, is introspective, an abused child who confides her pain to her diary. Instant soulmates, the two embark on one wild day of mischief, culminating, they insist, on murder “for fun.”

The critical notice Fun received while travelling the film festival circuit is due to Zielinski’s use of cinema verité techniques, which underscore the film’s gritty power. “The actors were really frustrated that I wasn’t telling them what to do,” says Zielinski, who asked the actors to perform as if they were doing the scenes in real life, while he followed them like a documentary filmmaker. “They had work twice as hard to become those people — which is what I think made their performances so incredible.”

There is also a kind of displaced autobiography in Fun, derived from the circumstances of Zielinski’s childhood. His mother uncovered that she was born of a Karaite Jewish sect, founded in the eighth century, that challenged the authority of the rabbinate. She met her Polish husband, a civil engineer, while both were students in Warsaw. “She’s the left side of the brain; he’s the right side,” Zielinski mentioned fondly. “They’re like salt and pepper.”

There is also a kind of displaced autobiography in Fun, derived from the circumstances of Zielinski’s childhood. His mother uncovered that she was born of a Karaite Jewish sect, founded in the eighth century, that challenged the authority of the rabbinate. She met her Polish husband, a civil engineer, while both were students in Warsaw. “She’s the left side of the brain; he’s the right side,” Zielinski mentioned fondly. “They’re like salt and pepper.”

Their backgrounds gave Zielinski “a sort of conflict that is always in myself. Karaism believes in righteousness, social justice, and the strict interpretation of the original written texts, whereas the romantic Slavic side is Chopin and music, excitement and the thrill of breaking rules. I tried to use those two opposing forces in the movie.”

Born in Poland, Zielinski moved to the United States with his parents when he was 7, then traveled in the Middle East and Southeast Asia where his father, employed by the Ford Foundation, built prefabricated housing. In Hong Kong, his father bought him an 8 mm camera; their peripatetic life made the boy feel like a “dysfunctional voyeur.” He never belonged anywhere but became “like a chameleon, immediately able to become part of any culture, but at the same time, totally alone,”

A stint In India in the late sixties altered his life: “Calcutta is the hellhole of the world with millions of homeless, diseased people. You see death every day, but the music and the Eastern mysticism were completely overwhelming.”

Today, he feels that Buddhism is the only rational explanation to the meaning of life and death. That impression was reinforced when he was sent to school in England at 13 and first read the Tibetan Book of the Dead, “It’s a prayer that talks about eternity between the moment you die and the moment you’re reborn.”

The route to feature filmmaking was circuitous for Zielinski. He first went to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology because he thought the future of art was in technology, only to find that computers were still too primitive to realize his artistic vision. After receiving a Bachelor of Science degree in Art and Design, he took graduate film studies at Concordia University in Montreal, then moved to Toronto, where he wound up making several films of dubious distinction (Loose Screws, Recruits and Screwballs among them) for the granddaddy of schlock, Roger Corman (The Wild Angels, The Pit and the Pendulum).

“I was young and didn’t realize the damage I was doing to my image and career,” he says now, philosophically. “I instantly got labeled asthat type of filmmaker. I hated the movies I made and the Toronto film community looked down on me. They didn’t appreciate Roger Corman. In Hollywood at least when people heard you worked for Corman, they’d say, ‘That’s great!’ but in Canada they were very snobby.”

In 1989, Zielinski finally got to make a film he cared about. Ginger Ale Afternoon, a romantic comedy, based on a play by Gina Wendkos, about a day in a trailer park couple’s life as they await the birth of their first child. It premiered at Sundance and got a theatrical release through Skouras Pictures.

With Fun, Zielinski first tried unsuccessfully to get investors to provide $2-million in financing and bring in some Hollywood stars. Eventually, he dug into his own pockets to shoot a three-day sketch to show to potential investors. However, he was so pleased with the footage that he did film, that he shot for another eight days, secured some backers and completed the film. Cost? $650,000 (U.S.).

He found his two “stars” by accident. When called in mid-scream to finishing directing Jail Bait, a formula Hollywood film, he was struck by Humphrey’s performance as a runaway girl on the streets of Los Angeles, as well as her “gritty beauty and raw energy.” Witt was found playing the piano in the Beverly Wilshire hotel; Zielinski was attracted to her because she seemed “so hypnotized” by the music. In the eighties, she had made her film debut in David Lynch’s Dune and his TV series Twin Peaks.

Seemingly senseless violence has become a profitable staple of contemporary filmmaking, but Zielinski would rather not be classed in the Quentin Tarantino camp. “Whenever there’s a crime, it’s splashed across the TV screen. The more violence we see on TV, the more violence on the street and more TV coverage of that violence. On top of that, movies fictionalize violence, which I think, promotes more real violence…

“Quentin Tarantino uses violence in an unconscious way, accentuating the fun and excitement, but ultimately I think that’s damaging. I don’t think he’s using it in a conscious way to understand what’s happening in our climate and how it’s affecting the souls of human beings.”